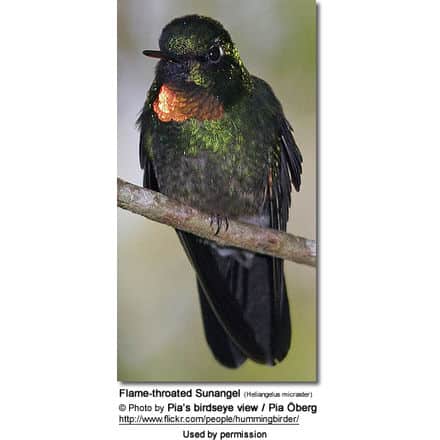

Flame-throated or Little Sunangels

The Flame-throated Sunangels (Heliangelus micraster) – also commonly known as the Little Sunangels – are South American hummingbirds.

They were previously considered one species with the Tourmaline Sunangels (Heliangelus exortis), but in 2005 the South American Classification Committee (SACC) decided to split them into Heliangelus exortis (Tourmaline Sunangels) and Heliangelus micraster (Flame-throated or Little Sunangel).

Distribution / Habitat

The Flame-throated Sunangels occur naturally in Ecuador and Peru where they inhabit dense mossy forests and forest borders at elevations between 7,545 – 11,155 feet (2,300 – 3,400 meters).

They are presumed sedentary except for some latitudinal movements in response to weather conditions and the availability of food sources.

Subspecies and Ranges:

Heliangelus micraster micraster (Gould, 1872) – Nominate Species

- Range: Found along the eastern Andean slope of southeastern Ecuador and adjacent N Peru

Heliangelus micraster cutervensis (Simon, 1921) – Subspecies

- Range: Northwestern Peru (Cajamarca).

Description

Flame-throated Sunangels measure 3.9 – 4.3 inches (10 – 11 cm) in length.

The male has an iridescent gorget (throat patch) that usually appears yellow-orange to red, but when viewed at certain angles, looks bright green. The chin is bluish bordered below by dark metallic green. The forehead is glossy green. The back is dark metallic green. The abdomen is greyish changing to white towards the forked tail. The tail is dark steel blue above and white below. The bill is straight and dark.

The female lacks the throat patch. Their throat can sometimes appear all white.

Similar Species: The male Tourmaline Sunangel (Heliangelus exortis) can be differentiated by his purplish gorget (throat patch), which is orange in the Flame-throated Sunangel.

Hummingbird Resources

- Hummingbird Information

- Hummingbird Amazing Facts

- Attracting Hummingbirds to Your Garden

- Hummingbird Species

- Feeding Hummingbirds

Diet / Feeding

The Flame-throated Sunangels primarily feed on nectar taken from a variety of brightly colored, scented small flowers of trees, herbs, shrubs, and epiphytes. They favor flowers with the highest sugar content (often red-colored and tubular-shaped) and seek out, and aggressively protect, those areas containing flowers with high-energy nectar. They use their long, extendible, straw-like tongues to retrieve the nectar while hovering with their tails cocked upward as they are licking at the nectar up to 13 times per second. Sometimes they may be seen hanging on the flower while feeding.

Many native and cultivated plants on whose flowers these birds feed heavily rely on them for pollination. The mostly tubular-shaped flowers actually exclude most bees and butterflies from feeding on them and, subsequently, from pollinating the plants.

They may also visit local hummingbird feeders for some sugar water, or drink out of bird baths or water fountains where they will either hover and sip water as it runs over the edge; or they will perch on the edge and drink – like all the other birds; however, they only remain still for a short moment.

They also take some small spiders and insects – important sources of protein particularly needed during the breeding season to ensure the proper development of their young. Insects are often caught in flight (hawking); snatched off leaves or branches, or are taken from spider webs. A nesting female can capture up to 2,000 insects a day.

Males establish feeding territories, where they aggressively chase away other males as well as large insects – such as bumblebees and hawk moths – that want to feed in their territory. They use aerial flights and intimidating displays to defend their territories.

Breeding / Nesting

Hummingbirds are solitary in all aspects of life other than breeding, and the male’s only involvement in the reproductive process is the actual mating with the female. They neither live nor migrate in flocks, and there is no pair bond for this species. Males court females by flying in a U-shaped pattern in front of them. He will separate from the female immediately after copulation. One male may mate with several females. In all likelihood, the female will also mate with several males. The males do not participate in choosing the nest location, building the nest or raising the chicks.