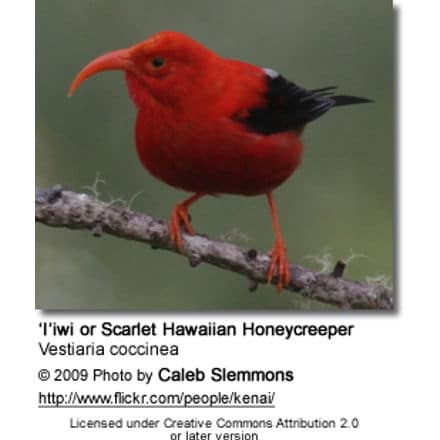

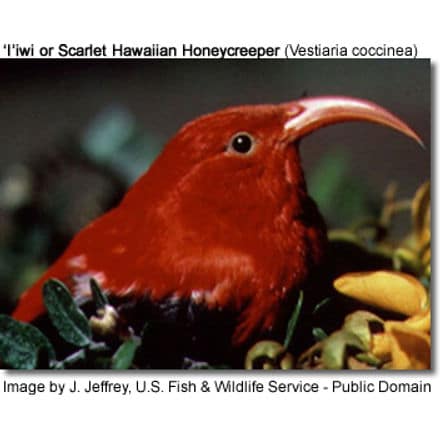

I’iwi or Scarlet Hawaiian Honeycreeper

The ‘I’iwi or Scarlet Hawaiian Honeycreeper (Vestiaria coccinea) is a Hawaiian finch in the Hawaiian honeycreeper subfamily, Drepanidinae, and the only member of the genus Vestiaria.

One of the most plentiful species of this family, many of which are endangered or extinct, the ‘i’iwi is a highly recognizable symbol of Hawai’i. The ‘i’iwi is the third most common native land bird in the Hawaiian Islands.

There are large colonies of ‘i’iwi on the islands of Hawai’i and Kaua’i, and smaller colonies on Moloka’i and O’ahu; ‘i’iwi were extirpated from L?na’i in 1929. Altogether, the remaining populations add up to a total of 350,000 birds.

Description and Uses

The adult ‘i’iwi is mostly fiery red, with black wings and tail and a long, curved, salmon-colored bill used primarily for drinking nectar. The contrast of the red and black plumage with surrounding green foliage makes the ‘i’iwi one of the most easily seen Hawaiian birds.

Younger birds have a more spotted golden plumage and ivory bills and were mistaken for a different species by early naturalists on Hawai’i. The ‘i’iwi, even though it was used in the feather trade, was less affected than the Hawai’i mamo because the former was not as sacred to the Hawaiians.

The ‘i’iwi’s feathers were highly prized by Hawaiian ali’i (nobility) for use in decorating ‘ahu’ula (capes) and mahiole (helmets), and such uses gave the species its scientific name: vestiaria, which comes from the Latin for clothing, and coccinea means scarlet-colored.

The bird is also often mentioned in Hawaiian folklore. The Hawaiian song “Sweet Lei Mamo” includes the line “The i’iwi bird, too, is a friend”. The bird is capable of hovering in the air, much like hummingbirds. Its peculiar song consists of a couple of whistles, the sound of balls dropping in water, the rubbing of balloons together, and the squeaking of a rusty hinge.

Diet

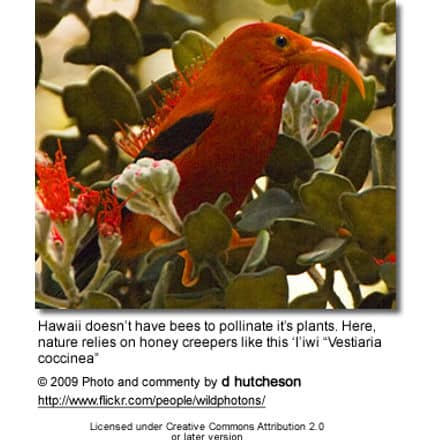

The long bill of the ‘i’iwi assists it to extract nectar from the flowers of the Hawaiian lobelioids, which have decurved corollas. Since 1902, the lobelioid population has declined dramatically, and the diet of the ‘i’iwi shifted to nectar from the blossoms of ‘?hi’a lehua (Metrosideros polymorpha) trees. ‘I’iwi also eat small arthropods.

Breeding

In the early winter in January to June, the birds pair off and mate as the ‘?hi’a plants reach their flowering maximum.

The female lays two to three eggs in a small cup shaped nest made from tree fibers, petals, and down feathers. These bluish eggs hatch in fourteen days. The chicks are yellowish-green marked with brownish-orange.

The chicks fledge in twenty-four days and soon attain adult plumage. At one time the difference in appearance between adults and young gave rise to the belief that they were separate species. Observations of young birds moulting into adult plumage resolved this confusion.

Threats and conservation

Although ‘I’iwi are still fairly common on most of the Hawaiian islands, it is rare on O’ahu and Moloka’i and no longer found on L?na’i. Most of the decline is blamed on loss of habitat, as native forests are cleared for farming, grazing, and development.

Even though it is still plentiful in two parts of its range, it is still listed as a threatened species because of small populations in some of its range and susceptibility to fowlpox and avian influenza.

In fact a study has shown that ninety percent of all exposed ‘I’iwi die and the other ten percent were weakened but survived.

However scientists have been helping restore the island ecosystem by removing alien or non-native species of plants and animals from critical habitat. Many of these so called removal projects have been done on the Big Island of Hawai’i, where efforts continue around Mauna Kea.

Populations of lobelia species have declined over the years and because of this the birds are increasingly being found at ‘?hi’a trees.

Another threat has been the spread of introduced diseases, particularly avian malaria (Plasmodium relictum), which is spread by mosquitoes.

In a series of challenge experiments involving avian malaria, more than half of the ‘I’iwi tested died from a single infected mosquito bite. Thus the ‘I’iwi generally survives at higher elevations where temperatures are too cool for mosquitoes, and like many disease-susceptible endemic birds is rare to absent at lower elevations, even in relatively intact native forest.

The ‘I’iwi were also removed when the islands forests were cut down and were replaced with farms, plantations, towns, and alien forests.

These birds are altitudinal migrants; they follow the growth of flowers as they go from high elevation to low elevation forests. It is thus exposed to harmful low elevation disease organisms and high mortality

This migration also makes it hard to assess the total populations on the islands. The birds are able to migrate between islands and it is because of this that the ‘I’iwi has not gone extinct on smaller islands such as Moloka’i.

On Moloka’i, The Nature Conservancy has attempted to preserve habitat by fencing off areas within several nature reserves to keep out pig populations. The pigs create wallows (pools of water or mud ) which serve as incubator sites for mosquito larvae, which in turn spread avian malaria.

It was formerly classified as a Near Threatened species by the IUCN, but recent research has proven that it was rarer than previously believed. Consequently, it was uplisted to Vulnerable status in 2008.

Beauty Of Birds strives to maintain accurate and up-to-date information; however, mistakes do happen. If you would like to correct or update any of the information, please contact us. THANK YOU!!!