Gyrfalcon (Falco rusticolu)

The gyrfalcon or Falco rusticolus, also spelled gerfalcon, is the largest of all falcon species. The Gyrfalcon breeds on Arctic coasts and islands of North America, Europe, and Asia.

It is mainly resident, but some Gyrfalcons disperse more widely after the breeding season, or in winter.

The bird’s common name comes from the French gerfaucon, and in medieval Latin is rendered as gyrofalco. The first part of the word may come from Old High German gîr (cf. modern German Geier), “vulture“, referring to its size compared to other falcons, or the Latin g?rus (“circle”, “curved path”) from the species’ circling as it searches for prey, unlike the other falcons in its range.

The male gyrfalcon is called a gyrkin in falconry.

Its scientific name is composed of the Latin terms for a falcon, Falco, and for someone who lives in the countryside, rusticolus.

Description

This species is a very large falcon, about the same size as the largest buteos.

Males are 48 to 61 cm (19 to 24 in) long, weigh 805 to 1350 g (1.8 to 3 lbs), and have a wingspan from 110 to 130 cm (43 to 51 in).

Females are rather bulkier and larger at 51 to 65 cm (20 to 26 in) long, have a weight of 1180 to 2100 g (2.6 to 4.6 lbs), and have a wingspan ranging from 124 to 160 cm (49 to 64 in).

In dimensions, gyrfalcons lie between a large Peregrine Falcon and a hawk in the general structure; they are unmistakably falcons with pointed wings but are stockier, broader-winged, and longer-tailed than the Peregrine.

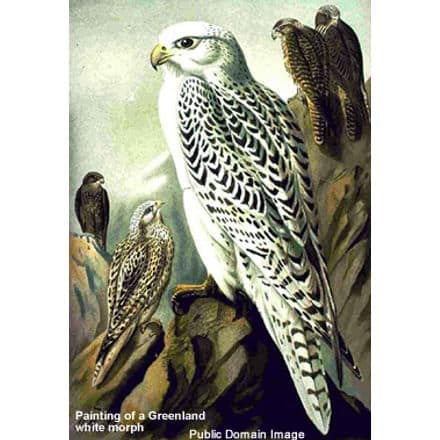

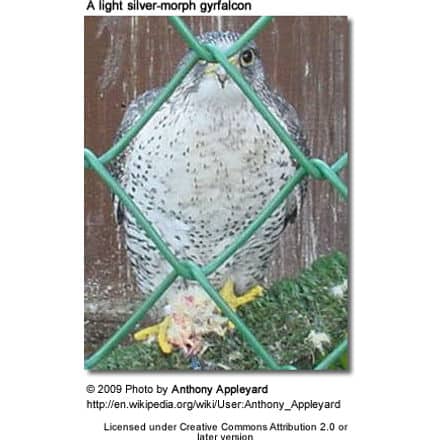

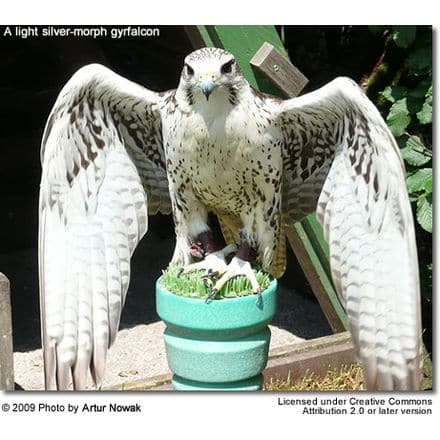

The plumage is very variable in this highly polymorphic species: the archetypal morphs are called “white”, “silver”, “brown” and “black” though coloration spans a continuous spectrum from nearly all-white birds to very dark ones.

The brown form of the Gyrfalcon is distinguished from the Peregrine by the cream streaking on the nape and crown and by the absence of a well-defined (cheek) stripe and cap. The black morph (genetic mutation) has its underside strongly spotted black, not finely barred as in the Peregrine.

White-form Gyrfalcons are unmistakable, as they are the only predominantly white falcons. Silver birds resemble a light, grey Lanner Falcon of huge size.

There is no difference in coloring between between males and females; juveniles are darker and browner than corresponding adults on average.

Systematics and evolution

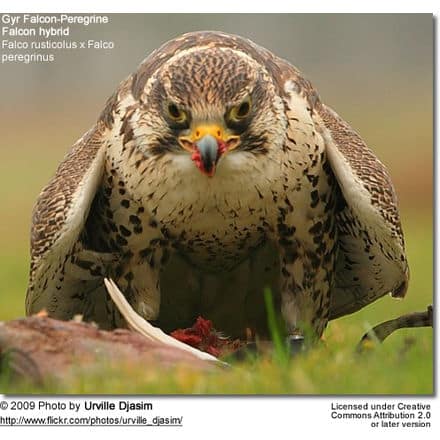

The Gyrfalcon is a member of the close-knit hierofalcon complex.

In this group, there is ample evidence for rampant hybridization and incomplete lineage sorting which confounds analyses of DNA sequence data to a massive extent; molecular studies with small sample sizes can simply not be expected to yield reliable conclusions in the entire hierofalcon group.

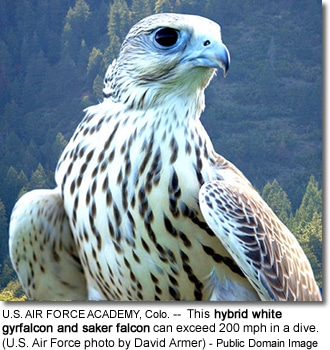

The radiation of the entire living diversity of hierofalcons seems to have taken place in the Eemian Stage at the start of the Late Pleistocene, a mere 130,000-115,000 years ago; the Gyrfalcon seems to represent lineages that expanded into the Holarctic and adapted to local conditions, whereas the inland populations further south, towards northeastern Africa where the radiation probably originated, evolved into the Saker Falcon.

Indeed, gyrfalcons hybridize not infrequently with Sakers in the Altay Mountains, and this gene flow seems to be the origin of the “Altai Falcon”.

Subspecies

There is some correlation between locality and the frequency of color morphs. Greenland Gyrfalcons are lightest, with white plumage flecked with grey on the back and wings being the most common.

Other subpopulations have varying amounts of the darker morphs: the Icelandic birds tend towards pale, and the Eurasian ones are considerably darker and do not usually have white birds present.

Natural separation into regional subspecies is prevented by Gyrfalcons’ habit of flying long distances exchanging alleles between subpopulations; thus, the allele distributions for the color polymorphism form clines and in darker birds of unknown origin, theoretically any allele combination might be present.

For example, a mating of a pair of captive Gyrfalcons is documented to have produced a clutch of 4 young: one white, one silver, one brown, and one black.

In general, geographic variation follows Bergmann’s Rule for size and the demands of crypsis for plumage coloration. Several subspecies have been named according to perceived differences between populations but none of these are consistent and thus no living subspecies are accepted today.

Perhaps the Icelandic population described as Falco rusticolus islands is the most distinct.

The predominantly white Arctic forms are parapatric and seamlessly grade into the subarctic populations, whereas the birds of Iceland have presumably less gene flow with their neighbors and indeed show less variation in plumage colors and often look quite similar to a large, washed-out Peregrine Falcon (though their habitus is different).

Comprehensive phylogeographic studies are needed to determine the proper status of the Icelandic population, however.

There was, however, a paleosubspecies Falco rusticolus swarthi during the Late Pleistocene (125,000 – 13,000 years ago). Fossils found in Little Box Elder Cave (Converse County, Wyoming), Dark Canyon Cave (Eddy County, New Mexico), and McKittrick, California were initially described as Falco swarthi (“Swarth Falcon” or more properly Swarth’s Gyrfalcon) on account of their distinct size. They have meanwhile proven to be largely inseparable from those of living gyrfalcons, except for being somewhat larger.

Swarth’s Gyrfalcon was on the upper end of the present Gyrfalcon’s size range, with strong females even surpassing it (Miller 1935). It seems to have had some adaptations to the temperate semiarid climate that predominated in its range during the last ice age.

Ecologically more similar to the Siberian populations of today (which are generally small birds however) or the Prairie Falcon, this population of temperate steppe habitat must have preyed on land birds and mammals rather than the water- and seabirds that make up much of American gyrfalcon’s diet today.

Ecology

The Gyrfalcon is a bird of tundra and mountains, with cliffs or a few patches of trees. It feeds only on birds and mammals. Like other hierofalcons, it usually hunts in a horizontal pursuit, rather than the Peregrine’s speedy stoop from a height.

Most prey is killed on the ground, whether they are captured there or if the victim is a flying bird, forced to the ground.

The diet is to some extent opportunistic, but a majority of breeding birds mostly rely on Lagopus grouse.

Avian prey can range in size from redpolls to geese and can include gulls, corvids, smaller passerines, waders, and other raptors (up to the size of Buteos).

Mammalian prey can range in size from shrews to marmots (sometimes 3 times heavier than the assaulting falcon), and often includes include lemmings, voles, ground squirrels, and hares. They only rarely eat carrion.

Reproduction and life history

The Gyrfalcon almost invariably nests on cliff faces. Breeding pairs do not build their own nests and often use a bare cliff ledge or the abandoned nest of other birds, particularly Golden Eagles and Common Ravens.

The clutch can range from 1 to 5 eggs but is usually 2 to 4. The average size of an egg is 58.46 x 45 mm (2.31 x 1.8 in) and the average weight is 62 g (2.2 oz). The incubation period averages 35 days until the 52 g (1.8 oz) chicks hatch.

The nestlings are brooded usually for 10 to 15 days and leave the nest at 7 to 8 weeks. At 3 to 4 months of age, the immatures become independent of their parents, though they may associate with their siblings through the following winter.

The only natural predators of gyrfalcons are Golden Eagles and even they rarely engage with these formidable falcons. Gyrfalcons have been recorded as aggressively harassing animals that come near their nests, although Common Ravens are the only predators known to successfully pick off Gyrfalcon eggs and hatchlings.

Even Brown Bears may be dive-bombed, much to their annoyance. Humans, whether accidentally (automobile collisions or poisoning of carrion to kill mammalian scavengers) or intentionally (through hunting), are the leading cause of death for Gyrfalcons.

Gyrfalcons that make it to adulthood can live up to 20 years of age.

As F. rusticolus has such a wide range, it is not considered a threatened species by the IUCN. It is not much affected by habitat destruction, but pollution e.g. by pesticides had depressed its numbers in the mid-20th century, and until 1994 it was considered Near Threatened.

Improved environmental standards have allowed the birds to make a comeback, and today they are not rare in most of their range.

Relationship with humans

The Gyrfalcon is the official bird of Canada’s Northwest Territories. The White falcon in the crest of the Icelandic Republic’s coat of arms is a variety of this species.

In medieval times, the Gyrfalcon was considered the king’s bird. Due to its rarity and the difficulties involved in obtaining it, in European falconry the gyrfalcon was generally reserved for kings and nobles. Very seldom was a man of lesser rank seen with a Gyrfalcon on his fist.

Gyrfalcons are very expensive to buy, and thus owners and breeders may keep them secret to avoid theft. They tend to fly long distances, and falconers may fit a radio-tracker to aid recovery.

Wild Gyrfalcons are not much exposed to disease, and as a result, have weak immune systems. As a result, many gyrfalcons taken from the wild quickly die of disease. Several generations of captive breeding from the survivors cause selection for a stronger immune system and thus better resistance to disease.