Eurasian Sparrowhawks or Northern Sparrowhawks

The Eurasian (or Northern) Sparrowhawks (Accipiter nisus) is a small bird of prey in the family Accipitridae which also includes many other diurnal raptors such as eagles, buzzards and harriers and other sparrowhawks.

Overview

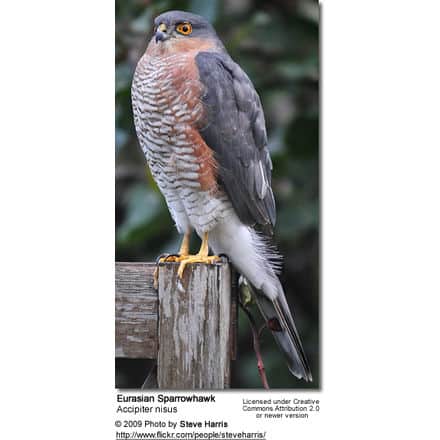

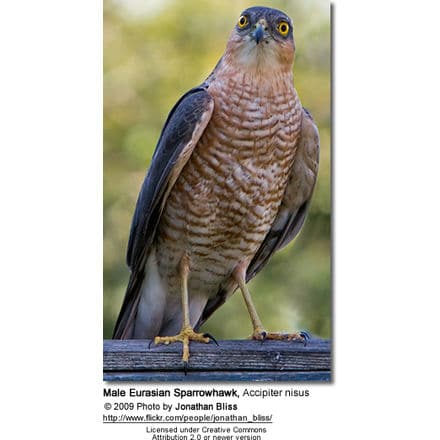

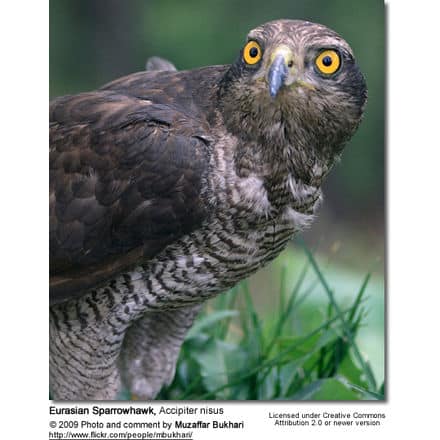

Adult male Eurasian Sparrowhawks have bluish grey upperparts and orange-barred underparts; females and juveniles are brown above with brown bars below. The male is up to 25 % smaller than the female – the largest difference between the sexes in any bird species.

It is now one of the most common birds of prey in Europe, but the population crashed after the Second World War. Organochlorine insecticides used to treat seeds prior to sowing built up in the bird population and the concentrations in Eurasian Sparrowhawks were enough to kill some outright and incapacitate others; affected birds laid eggs with fragile shells which broke during incubation.

It is a predator which specialises in catching woodland birds, but it can be seen in any habitat and hunts garden birds in towns and cities. Male Eurasian Sparrowhawks tend to take tits, finches and sparrows; females catch thrushes and starlings but are capable of killing birds weighing 500 g or more. Eurasian Sparrowhawks breed in suitable woodland of any type.

Description

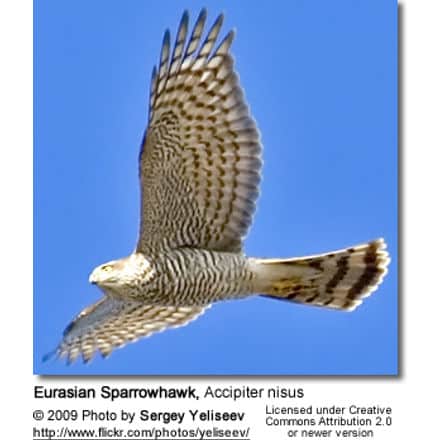

This bird is a small raptor with short, broad wings and a long tail, both adaptations to manoeuvring through trees. Female Eurasian Sparrowhawks can be up to 25 % larger than males – the largest difference between the sexes in any bird species. The throat has dark streaks and lacks a mesial stripe.

The adult male is 29-34 cm long with a 59–64 cm wingspan, and is slate-grey above (though some are more bluish). The underparts are finely barred reddish, looking plain orange from a distance; his irides are orange-yellow or orange-red. He weighs between 131-180 g. The female is much larger at 35-41 cm in length with a 67-80 cm wingspan, weighing between 186-345 g. She has dark brown, or greyish-brown, upperparts and brown-barred underparts, and bright yellow to orange eyes. The juvenile is warm brown above, with rusty fringes to the upperparts and coarsely barred or spotted brown below, with pale yellow eyes. All have long, yellow legs with black claws.

The flight is a characteristic “flap-flap-glide”, with the glide creating an undulating pattern. This species is similar in size to the Levant Sparrowhawk but bigger than the Shikra; the male is only slightly bigger than the Merlin. Because of the overlap in sizes, the female can be confused with the similarly-sized male Northern Goshawk, but lacks the bulk of that species. Eurasian Sparrowhawks are smaller, more slender and have shorter wings, a square-ended tail and fly with faster wingbeats.

The oldest recorded ringed Eurasian Sparrowhawk in Europe was a bird trapped in Denmark which was 20 years, 3 months old. The typical lifespan is three years. Data analysis by the British Trust for Ornithology shows that the proportion of juveniles surviving their first year of life is 39 %; adult survival from one year to the next is 65.7 %. A study of female Eurasian Sparrowhawks found “strong evidence” that their rate of survival increased for the first three years of life and declined for the last five to six years. Senescence (ageing) was the cause of the decline as the birds became older.

Taxonomy

The scientific name is derived from the Latin accipiter, meaning ‘hawk’ and nisus, the sparrowhawk.

Six subspecies are generally recognized:

- A. n. nisus, described by Carolus Linnaeus in 1758. Breeds in Europe and west Asia to western Siberia and Iran; northern populations winter south to the Mediterranean, north-east Africa, Arabia and Pakistan

- A. n. nisosimilis, described by Samuel Tickell in 1833. Breeds in central and eastern Siberia east to Kamchatka and Japan, and south to north China; wholly migratory, wintering from Pakistan and India east through South-East Asia and south China to Korea and Japan, some even reaching Africa

- A. n. melaschistos, described by Allan Octavian Hume in 1869. Breeds in mountains from Afghanistan through the Himalaya and south Tibet to west China and winters in the plains. It is longer tailed than nisosimilis.

- A. n. wolterstorffi,described by Otto Kleinschmidt in 1900. Resident Sardinia and Corsica. Smaller, darker on upperparts and more barred

- A. n. granti, described by Richard Bowdler Sharpe in 1890. Resident Madeira and Canary Islands

- A. n. punicus, described by Erlanger in 1897. Resident north-west Africa north of the Sahara. Very similar to nisus.

Accipiter nisus forms a superspecies with East and Southern African Rufous-chested Sparrowhawk, A. rufiventris and possibly Madagascar Sparrowhawk, A. madagascariensis

Distribution and habitat

It is a widespread species throughout the temperate and subtropical parts of the Old World. Birds from colder regions of north Europe and Asia migrate south for the winter, some to north Africa (some as far as equatorial east Africa) and India; members of the southern populations are resident or disperse. Juveniles begin their migration earlier than adults and juvenile females move before juvenile males.

Analysis of Heligoland, Germany, ringing data found that males move further and more often than females; of birds ringed at Kaliningrad, Russia, the average distance moved before recovery (when a bird is caught again by another ringer, or the ring read) was 1,328 km for males and 927 km for females. A study of Eurasian Sparrowhawks in southern Scotland found that ringed birds which had been raised on “high grade” territories were recovered in greater proportion than birds which came from “low grade” territories. This suggested that the high grade territories produced young which survived better. The recovery rate also declined with increased elevation of the ground. After the post-fledging period, female birds dispersed greater distances than did males.

The Eurasian Sparrowhawk has an estimated global Extent of Occurrence of between 100,000-1,000,000 square km and an estimated world population of 1 million to 10 million birds; it is one of the most common birds of prey in Europe, along with the Common Kestrel and Common Buzzard. Though global population trends have not been analysed, numbers seem to be stable, so the Eurasian Sparrowhawk has been classified as Least Concern by the BirdLife International. The race granti, with 100 pairs resident on Madeira and 200 pairs on the Canary Islands, is threatened by loss of habitat, egg-collecting and illegal hunting and is listed on Annex I of the European Commission Birds Directive.

This species is common in most woodland types in its range and also in more open country with scattered trees. Eurasian Sparrowhawks prefer to hunt woodland edges, but migrant birds can be seen in any habitat. Unlike its larger relative the Northern Goshawk, it can be seen in gardens and in urban areas and will even breed in city parks.

Food and feeding

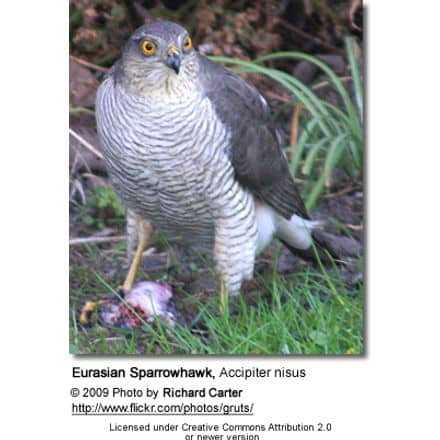

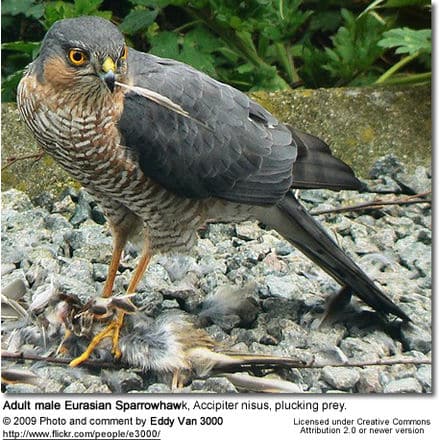

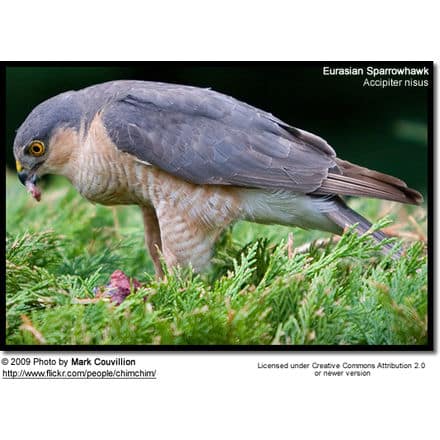

The Eurasian Sparrowhawk is a main predator of smaller woodland birds. During hunting, this species can fly 2-3 km per day. It rises above tree level mostly to display, soar above territory and to make longer journeys.[3] It hunts by surprise attack, using hedges, tree-belts, copses, orchards and other cover near woodland areas; their choice of habitat is dictated by these requirements. It waits, hidden, for birds to come near, and then breaks cover and flies out fast and low. A chase may follow, with the hawk even flipping upside-down to grab the victim from below or following it on foot through vegetation. It can “stoop” onto prey from a great height. Eurasian Sparrowhawks do not hesitate to make use of gardens in built-up areas and take advantage of the prey found there.

Male Eurasian Sparrowhawks regularly kill birds weighing up to 40 g and sometimes up to 120 g; females can tackle prey up to 500 g or more. The weight of food consumed by adult birds is estimated to be 40-50 g for males and 50-70 g for females. The species taken are those whose behaviour makes them easy targets. Males tend to take tits, finches, sparrows and buntings; females often take thrushes and starlings. Larger quarry (such as doves and magpies) may not die immediately but succumb during feather plucking and eating. More than 120 bird species have been recorded as prey and individual Eurasian Sparrowhawks may specialise in certain prey. The birds taken are usually adults or fledglings, though chicks in the nest and carrion are sometimes eaten. Small mammals are sometimes caught but Eurasian Sparrowhawks eat insects only very rarely.

A study of the prey of Eurasian Sparrowhawks suggested that changes in the behaviour of prey species living in semi-open habitats during May and June put them at greater risk of predation, rather than changes in vegetation at that time. Another study looked at the effect on the population of Blue Tits in an area when a pair of Eurasian Sparrowhawks began to breed there in 1990. It found that the annual adult survival rate for the tits in that area dropped from 0.485 to 0.376 (the rate in adjacent plots did not change), but that the size of the breeding population was not changed. There were fewer non-breeding Blue Tits in the population. Another study found that the risk of predation for a bird targeted by a Eurasian Sparrowhawk or Northern Goshawk increased 25-fold if the prey was infected with the blood parasite Leucocytozoon, and birds with avian malaria were 16 times more likely to be killed.

When eating, Eurasian Sparrowhawks pluck the feathers and usually eat the breast muscles first. The bones are left, but can be broken using the notch in the bill. Like other birds of prey, Eurasian Sparrowhawks produce pellets containing indigestible parts of their prey. They range from 25 to 35 mm long and 10-18 mm wide and are round at one end and more narrow and pointed at the other. They are usually composed of small feathers, as the larger ones are plucked and not consumed.

Breeding

The Eurasian Sparrowhawk breeds in well-grown, extensive areas of woodland, often coniferous or mixed. An structure neither too dense or too open is preferred, to allow a choice of flightpaths. The nest can be located in the fork of a tree, often near the trunk and where two or three branches begin, on a horizontal branch in the lower canopy, or near the top of a tall shrub. If they are available, conifers are preferred. A new nest is built every year, with the male doing most of the work, close to that of the previous year and sometimes using an old Woodpigeon nest as a base. The structure of loose twigs (up to 60 cm long) has an average diameter of 60 cm. When the eggs are laid, a lining of fine twigs or bark chippings is added.

A single clutch of four or five eggs is laid; each egg measures 40 x 32 mm and weighs 22.5 g, of which 8 % is shell. The eggs are mostly laid in the morning, with 2-3 days between each one. If a clutch is lost, up to two replacements may be laid, but they are always smaller than the original.

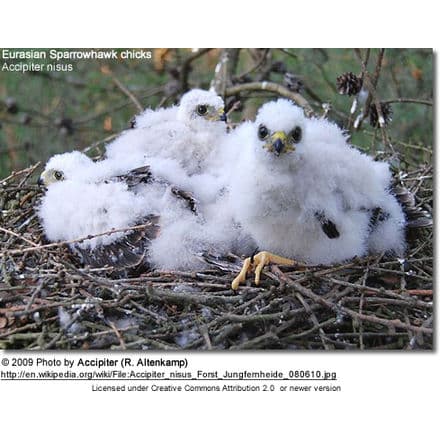

The altricial, downy chicks hatch after 33 days of incubation and fledge after between 27 and 31 days. After hatching, the female cares for and feeds the chicks for the first 8-14 days of life, and also during bad weather after that. The male provides food, up to six kills per day in the first week increasing to eight per day in the third and 10 per day in the last week in the nest, by which time the female is also hunting. At between 24-28 days after hatching, the young birds start to perch on branches near the nest, though they remain dependent on their parents for 28-30 days after fledging.

Most Eurasian Sparrowhawks stay on the same territory for one breeding season, though others keep the same one for up to eight years. A change of mate usually triggers the change in territory. Older birds tend to stay in the same territory; failed breeding attempts make a move more likely. The birds which kept the same territories had higher nest success, though it did not increase between years; females which moved experienced more success the year after changing territory.

Relationship with humans

Pollutants

The Eurasian Sparrowhawk population in Europe crashed in the second half of the 20th Century. The decline coincided with the introduction of cyclodiene insecticides – aldrin, dieldrin and heptachlor – used as seed dressings in agriculture in 1956. The chemicals accumulated in the bodies of grain-eating birds and had two effects on top predators like the Eurasian Sparrowhawk and Peregrine Falcon: the shells of eggs they laid were too thin, causing them to break during incubation; and birds were poisoned by lethal concentrations of the insecticides. Sub-lethal effects of these chemicals include irritability, convulsions and disorientation, which would affect the birds’ hunting skills.

In the United Kingdom, for example, the species almost became extinct in East Anglia, where the chemicals were most widely used; in western and northern parts of the country, where the pesticides were not used, there were no declines. The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds bought its Coombes Valley nature reserve in Staffordshire because it was the only Eurasian Sparrowhawk breeding site left in the English Midlands.

In the UK, the use of cyclodienes as seed dressings for autumn-sown cereals was banned in 1975 and the levels of the chemicals present in the bird population began to fall. The population has largely recovered to pre-decline levels, with an increase seen in many areas, for example northern Europe. In the UK, the failure rate at the egg stage had decreased from 17 % to 6 % by the year 2000, and the population had stabilised after reaching a peak in the 1990s. A study of the eggs of Dutch sparrowhawks found that contamination with Dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (DDE) – a “very persistent compound” produced when DDT breaks down – continued into the 1980s, though a decline in the number of clutches with broken eggs during the 1970s suggested decreasing levels of the chemical.

Body tissue samples from Eurasian Sparrowhawks are still analysed as part of the Predatory Bird Monitoring Scheme conducted by the UK government’s Joint Nature Conservation Committee. Although the average liver concentrations of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in sparrowhawks were lower in birds that died in 2005 compared to those that died in 2004, there was not a significant or consistent decline in residues between 2000-2005.

Conflict with human interests

The Eurasian Sparrowhawk’s adaptation for feeding on birds has brought it into conflict with humans. In Europe, the species suffered heavy persecution by 19th Century landowners and gamekeepers, but withstood attempts to eradicate it in the United Kingdom and Ireland, for example. The species was able to quickly replace lost birds – the population has a high proportion of non-breeding, non-territorial birds able to fill vacant territories. For example, a total of 738 Eurasian Sparrowhawks were shot on a sporting estate near Betws-y-Coed in Caernarfonshire, Wales, between 1874-1902. The habitat conserved with gamebirds in mind also suited this species and its prey; gamekeepers’ more successful efforts to wipe out the Northern Goshawk and Pine Marten – predators of the Eurasian Sparrowhawk – may have benefited it. The population increased markedly when this pressure was relaxed, for example during the First and Second World Wars.

In February 2009, the Scottish Government began a trial relocation of Eurasian Sparrowhawks from around racing pigeon lofts in Glasgow, Edinburgh, Kilmarnock, Stirling and Dumfries. The trial, which costed £25,000, was supported by the Scottish Homing Union, representing the country’s 3,500 pigeon fanciers. The experiment was originally scheduled for early in 2008 but was postponed because it would have impinged on the birds’ breeding season. The plan was criticised by the government’s own ecological adviser, Dr Ian Bainbridge, Scottish Natural Heritage (funded by the government), and organisations including the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds[30] and the Scottish Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

Falconry

The Eurasian Sparrowhawk has been used in falconry for centuries and was favoured by Emperor Akbar the Great (1542-1605) of the Mughal Empire. There is a tradition of using migrant sparrowhawks to catch Common Quail in Tunisia and Georgia, where there are 500 registered bazieri (sparrowhawkers) and a monument to bazieri in the city of Poti. Sparrowhawks are also popular in Ireland. In England in the 17th century, the sparrowhawk was used by priests, reflecting their lowly status; in the Middle Ages, they were favoured by ladies of noble and royal status because of their small size.

In Falconry and Hawking, Philip Glasier described Eurasian Sparrowhawks as “definitely not birds for beginners…”, “in many ways superior to hunting with a larger short-wing [hawk]” and “extremely hard to tame.” They are best suited for small quarry such as Common Starlings and Common Blackbirds but are also capable of taking Common Teal, Eurasian Magpies, pheasants and partridges.

The falconer’s name for a male sparrowhawk is a “musket”; this is derived from the Latin word musca, meaning ‘a fly’, via the Old French word moschet. The musket, or musquet, originally a kind of crossbow bolt, and later a small cannon, was named after the bird because of its size.

- According to Greek mythology, Nisus, the king of Megara, was turned into a sparrowhawk after his daughter, Scylla, cut off his purple lock of hair to present to her lover (and Nisus’ enemy), Minos.

- In William Shakespeare’s The Merry Wives of Windsor, Mrs Ford greets Robin with the words “How now, my eyas musker, what news with you?”, musker meaning a lively young man.

- Old English folk names for this species include Blue Hawk, referring to the adult male’s colouration, and Spar Hawk, Spur Hawk and Stone Falcon.

- The name Spearhafoc (later Sparhawk, Sparrowhawk) was in use as a personal name in England before the Norman conquest in 1066.

- A story told at the British Association meeting at Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England, in 1863 said that a man criticised for shooting a Common Cuckoo justified his action by saying that it was well known that sparrowhawks turned into cuckoos in summer.

- The British Gloster Aircraft Company named one of their Mars series machines the Sparrowhawk.

- Hermann Hesse mentioned this bird in his book Demian.

- The Eurasian Sparrowhawk is referred to in One Thousand and One Arabian Nights by Richard Francis Burton

Beauty Of Birds strives to maintain accurate and up-to-date information; however, mistakes do happen. If you would like to correct or update any of the information, please contact us. THANK YOU!!!