Northern Spotted Owl (Strix occidentalis caurina)

The Northern Spotted Owl, Strix occidentalis caurina, is one of three Spotted Owl subspecies. It’s a Western North American bird in the family Strigidae, genus Strix.

There are documented individuals of 22 years of age in the wild, but the average lifespan can be considered 10 years of age.

Description

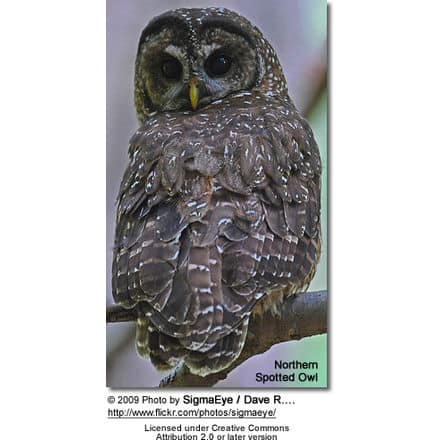

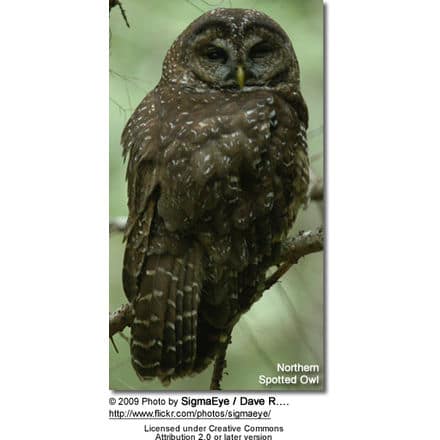

This is a medium-sized dark brown owl sixteen to nineteen inches in length and one to one and one-sixth pounds. The wingspan is approximately forty-two inches. Females are larger than males.

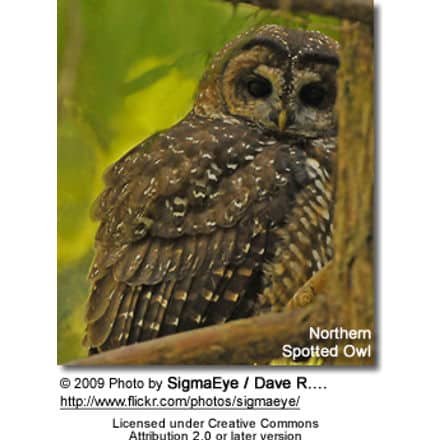

Northern Spotted Owls are dark brown with round or oval white spots on the head, neck, and back and have a whitish underbody with brown bars along the abdomen and chest.

Their flight feathers are dark brown and have light brown or white bars.

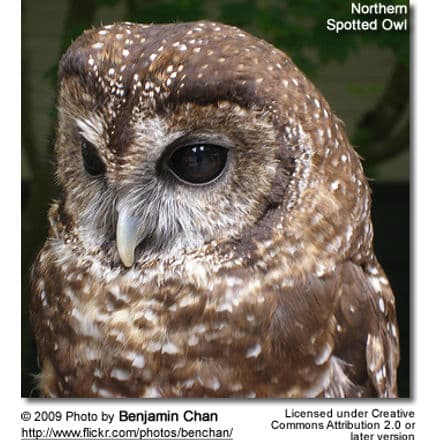

They have dark eyes contrary to most owls which have light eyes.

The facial disk has white feathers around the eyes running down each side of the beak.

Habitat

The Northern Spotted Owl primarily inhabits old-growth forests in the northern part of its range (Canada to southern Oregon) and landscapes with a mix of old and younger forest types in the southern part of its range (Klamath region and California).

The species’ range is the Pacific coast from extreme southern British Columbia to Marin County in northern California.

It nests in cavities or on platforms in large trees and will use abandoned nests of other species. Spotted owls mate for life and remain in the same geographical areas year after year.

Most Spotted Owls occur on US federal lands (Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, and National Park Service lands), although significant numbers occur on state lands in all three states, and on private and tribal properties.

Diet

The Northern Spotted Owl is primarily nocturnal. Its diet consists mainly of wood rats (Neotoma sp.) and flying squirrels, although it will also eat other small mammals, reptiles, birds, and insects.

They will often swallow their catch whole and regurgitate pellets of indigestible hair, feathers, and bones.

Males and females both hunt, except during nesting, when males do most of the hunting. They can take prey on the ground and in flight.

Behavior

The Northern Spotted Owl is very protective of their territory and intolerant of habitat disturbance.

Each nesting pair needs a large amount of land for hunting and nesting, and will not migrate unless they experience drastic seasonal changes, such as heavy snows, which make hunting difficult.

Their flight pattern is distinct, involving a series of rapid wingbeats interspersed with gliding flight. This technique allows them to glide silently down upon their prey.

Reproduction

Northern Spotted Owls are ready to reproduce at two years of age but do not typically breed until they are three years old.

Male and females mate in February or March and the female lays two or three eggs in March or April.

She then incubates the eggs for 30 days. After hatching, the young owls stay with the female for eight to 10 days and fledge in 34 to 36 days.

The hunting and feeding is done by the male during this time. The young owls remain with their parents until late summer to early fall.

They leave the nest and form their winter feeding range.

By spring, the young owls’ territory will be from two to 24 miles from the parents.

Threats

The greatest threat to spotted owl populations has historically been the loss of old-growth and mature late-seral forest, which contains large dead trees for nesting and prey habitat, as well as cool, dark roosts under the dense overstory canopy.

Fragmentation of remaining habitat results from logging and roads, and may have increased predation by Great Horned Owls and other species. More recently (since the 1960s), a related eastern species, the Barred Owl (Strix varia), has invaded the Pacific Northwest.

Barred owls are larger, more aggressive, and compete for both nest sites and food. They also occasionally attack spotted owls (and humans) and will mate and hybridize with spotted owls, but this has been documented to occur very rarely.

Barred Owls in the west occur in both young and old forests and are thought to displace spotted owls from their territories in old-growth and mature forests.

Additional threats to Spotted Owls include substantial loss of habitat to wildfire and forest diseases, and also the West Nile Virus.

Status

Approximately three to five thousand pairs are remaining in the wild, mostly in the states of Washington, Oregon, and California. The Canadian population now numbers less than 20 birds.

United States Fish and Wildlife Service reviewed the status of the Northern Spotted Owl in 1982 and 1987, finding it did not warrant listing as threatened or endangered.

Reviews in 1989 and 1990 proposed listing as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act throughout its range (northern California, Oregon, and Washington), citing loss of old-growth habitat as the primary threat.

This was implemented on 1990-06-23.[3] Logging in national forests was stopped by a court order in 1991.

Controversy

The logging industry estimated up to 30,000 of 168,000 jobs would be lost because of the owl’s status, which agreed closely with a Forest Service estimate.

Harvests of timber in the Pacific Northwest were reduced by 80%, decreasing the supply of lumber and increasing prices.

The decline in jobs was already in progress because of dwindling old-growth forest harvests and automation of the lumber industry.

Subsequent research at the University of Wisconsin-Madison by environmental scientists published in a sociology journal argued that logging jobs had been in a long decline and that environmental protection was not a significant factor in job loss.

From 1947 to 1964, the number of logging jobs declined by 90%. Starting with the Wilderness Act of 1964, environmental protection saved 51,000 jobs in the Pacific Northwest.

The controversy pitted individual loggers and small sawmill owners against environmentalists. Bumper stickers reading Kill a Spotted Owl—Save a Logger and I Like Spotted Owls—Fried appeared to support the loggers. Plastic spotted owls were hung in effigy in Oregon sawmills.

The logging industry, in response to continued bad publicity, started the Sustainable Forestry Initiative.

While timber interests and conservatives have cited the Northern Spotted Owl as an example of excessive or misguided environmental protection, many environmentalists view the owl as an “indicator species,” or “canary in a coal mine” whose preservation has created protection for an entire threatened ecosystem.

Protection of the owl, under both the Endangered Species Act and the National Forest Management Act, has led to significant changes in forest practices in the northwest.

President Clinton’s controversial Northwest Forest Plan of 1994 was designed primarily to protect owls and other species dependent on old-growth forests while ensuring a certain amount of timber harvest.

Although the result was much less logging, industry automation and the new law meant the loss of thousands of jobs.

The debate has cooled somewhat over the years, with little response from environmentalists as the owl’s population continues to decline by 3.7 percent per year.

Under the Bush administration, in 2004 the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service reaffirmed that the owl remained threatened, but indicated that the causes of endangerment had changed, mostly as a result of invasion by barred owls into the range and habitat of the spotted owl.

In 2007, the USFWS proposed new recovery plans intended to guide all management actions on lands where spotted owls occur and to aid in the recovery of the species.

Early proposals have been criticized by environmental groups as significantly weakening existing protections for the species.

At the same time, the Bush administration wants to lift restrictions on logging and other human activity in 23 percent of the land now designated as critical habitat for the spotted owl, citing research indicating that the species does not always require vast tracts of old-growth forest.

A new emphasis on control of barred owl populations through culling has been criticized, with at least one scientist on the USFWS recovery team calling this proposal “a deception to deflect blame away from habitat destruction”.

More Owl Information

- Owl Information

- Index of Owl Species with Pictures

- Owl Eyes / Vision Adaptations

- Pygmy Owls

- Barn Owls

- Horned Owls

- Scops Owls