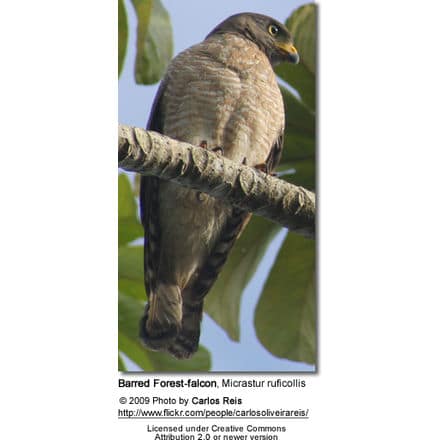

Barred Forest Falcon (Micrastur ruficollis)

The Barred Forest Falcon (Micrastur ruficollis) is a species of bird of prey in the Falconidae family which includes the falcons, caracaras, and their relatives.

It occurs throughout most of tropical and subtropical Latin America, except the arid Pacific coast in South America, northern and western Mexico, and the Antilles.

Description

Adults of most subspecies are typically dark slate grey above; the tail tipped with white and having three to six narrow white bars. The throat is pale grey, shading to the darker slate of the crown. The rest of his underparts, including the under-wing coverts are white, finely, and barred with black or dark grey. The upper breast is a darker grey. The primary remiges (flight feathers – typically only visible in flight) are dark brownish-grey with off-white bars on the inner webs.

One subspecies, zonothorax from the East Andean foothills, is polymorphic (at least in the northern part of its range), and also occurs in a brown morph (genetic mutation), where most of the upperparts, head, and chest are brown or rufous instead of grey.

The nominate subspecies, which is found from south-eastern Brazil south to north-eastern Argentina and west to Paraguay, appears to only occur in the rufous-brown morphotype, as also suggested by its scientific name, ruficollis.

The eyes are cream to light orange-brown; the bill black, becoming yellow at the base of the lower mandible; the cere, lores, and orbit are yellow, and the legs are orange-yellow.

Ecology

Barred Forest-falcons mainly utilize mature upland forests. In Central America, the species is generally restricted to mature tropical forests. In South America, however, the Barred forest falcon lives in other kinds of forests and woodland, even relatively arid. For example, in Amazonia, it occurs most often in secondary forests, gallery forests, tidal swamp forests, semi-deciduous forests, and forest edges. In Acre, Brazil, the Barred Forest-falcon is reported to prefer disturbed forest types, both natural secondary, and man-made, including bamboo and more open seasonally drier forests on rocky outcrops.

But generally, it is a bird that avoids habitat when human influence is too pronounced and will require primary or mature secondary forest to persist in any location. It is not commonly seen, but based on voice, it appears to be uncommon to fairly common throughout a large part of its range.

This combined with its large range has led to it being classified as a species of Least Concern by the IUCN.

It is rare on the eastern slope of the Colombian Cordillera Oriental, where it was recorded in primary forest and old secondary forest, in a narrow altitude band between 3,300-4,900 ft (1,000-1,500 m) ASL, and first encountered in the Serranía de las Quinchas only in 2000/2001. Second-growth forest in these mountains is dominated by trees like Melastomaceae (e.g. Miconia and Tibouchina) and trees are generally overgrown with epiphytes and hemiepiphytes like Coussapoa (Urticaceae).

Diet / Feeding

This species feeds primarily upon small birds, and mammals (mainly rodents and marsupials such as the Brazilian Slender Opossum, Marmosops paulensis, and squamates.

Like Accipiter hawks, they often hunt prey by sitting quietly on tree branches and waiting for their victims to appear. When the latter arrives, the forest falcons quickly ambush them, attempting to catch them with a brief, flying pursuit. However, forest falcons also use other techniques to hunt prey, such as chasing prey on foot, following army ant swarms, and acoustical luring of birds, using a “facial disc”. The species has also been recorded to snatch animals from traps or cages, for example during mark-recapture studies.

Nesting / Breeding

Forest falcons do not build a nest but lay their two or three white eggs in cavities in trees. Laying occurs mainly late in the dry season, with hatching taking place at the onset of the rainy season, a time of increasing prey abundance. Eggs hatch 33-35 days after being laid, and nestlings fledge 35-44 days after hatching.

Radio-tagged fledglings dispersed from their parents’ territories within four to seven weeks after fledging, presumably achieving independence at that time.

Nesting territories were occupied year after year; there was also high mate fidelity.