Berylline Hummingbirds (Amazilia beryllina)

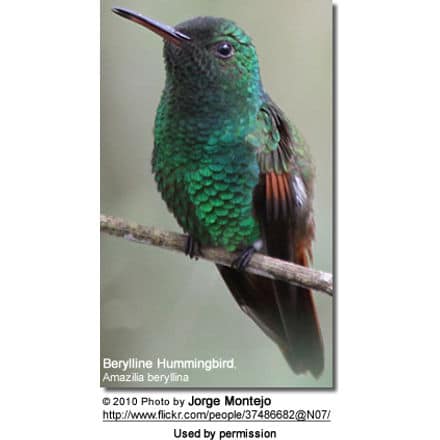

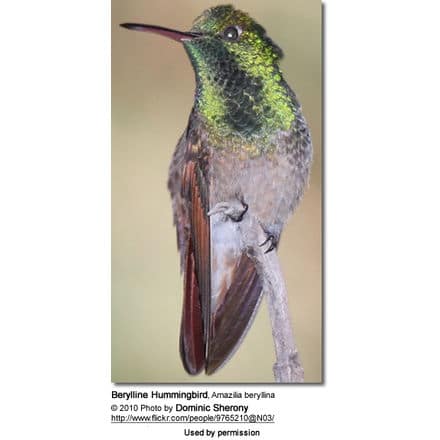

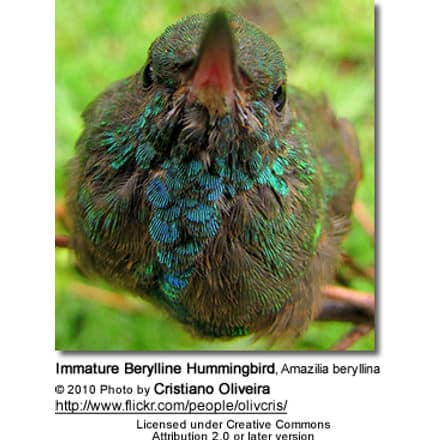

The Berylline Hummingbirds, Amazilia beryllina, sometimes placed in the genus Saucerottia) is named after the sea green gem beryl – as the dominant color of this bird closely resembles the color of this gem. (Berylline = like a beryl).

Alternate (Global) Names:

Spanish: Colibrí colicastaña, Amazilia Berilina, Colibrí Berilo, Colibrí colicastaña, Colibri de Berilo, Colibrí de Berilo … French: Ariane arsinoë, Ariane béryl, Colibri béryl … Italian: Amazilia berillina, Colibrì berillo … German: Beryll Amazine, Beryllamazilie, Beryllamazine … Czech: Kolibrík mexický, kolib?ík mexický … Danish: Berylamazilie … Finnish: Ruskotimanttikolibri … Japanese: kougenemerarudohachidori, kougen’emerarudohachidori … Latin: Amazilia beryllina, Ariane arsinoe, Saucerottia beryllina … Dutch: Berylkolibrie … Norwegian: Beryllkolibri … Polish: szmaragdzik berylowy … Russian: ?????????? ???????? … Slovak: kolibrík smaragdový … Swedish: Beryllkolibri

Subspecies:

- Saucerottia / Amazilia beryllina beryllina – Nominate Race (Lichtenstein, 1830)

- Found in Central Mexico

- Found in South Guatemala and El Salvador to Central Honduras

- Found in South Mexico (Western Chiapas)

- Found in South Mexico (Central and South Chiapas).

- Found in Northwestern and western Mexico. Rarely observed in southwestern USA (i.e., Arizona)

In A Guide to the Birds of Mexico and Northern Central America, Howell, and Webb, Howell split Beryllines into two groups (beryllina and devillei). He states that these two groups are as distinct as many currently recognized species and warrant taxonomic investigation.

Distribution / Range

The Berylline Hummingbirds occur in the United States (Arizona, New Mexico, Texas), Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. This hummingbird is essentially non-migratory.

They are endemic to the western and southern highlands and foothills of Mexico and northern Central America, south to Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. On the Atlantic Slope, it occurs locally from central Veracruz to Honduras.

As they don’t regularly breed in the United States, some sources list the Berylline Hummingbirds as an accidental species (non-native vagrants). Some authorities describe them as “rare, but regular visitors” to the “Mexican Mountains” with a few nesting records in the Madrean sky islands region.

The Berylline Hummingbirds is one of three hummingbird species found in Arizona and is among the rarer of southeastern Arizona’s hummingbird species.

In Texas, this species has been recorded in the Chisos Mountains (1 record); Davis Mountains (4 records); Cochise Canyon of the Davis Mountains (17 August through 4 September 1997; August 1999; 25 May – 16 July 2000; 25 – 28 August 2007). The first Texas record occurred on 18 August 1991 along the Juniper Trail near Boot Canyon, Chisos Mountains, Brewster County by John Trochet.

There have only been a few sightings in New Mexico.

Preferred Habitat: They prefer pine-oak and pine forests tropical deciduous forests and canyon thickets. They are very common in dry temperate forests and are often found near streams. They are usually found at an elevation from 3000 to 10000 feet (~ 900 – 3000 meters).

Behavior

These solitary and aggressive birds will fiercely defend their feeding territory and will chase intruders away from their favorite perching locations. They are common visitors found at hummingbird feeders.

Description

The Berylline Hummingbirds is a medium-sized hummingbird with a length of 8 to 11 cm (3 – 4.25 inches) long and weighs 4-5 g (0.14 – 0.18 oz). The male is slightly larger than the female, with an average weight of 4.87 g (0.17 oz) compared to 4.37 g (0.15 oz) of the female.

It has a distinctive bright iridescent turquoise-green head, throat, and chest that contrast against the darker cinnamon-red wings and tail. The lower abdomen is buff to whitish-gray.

The tail is dark with a purple-violet sheet. The undertail feathers can show a rufous tinge.

The bill is straight and slender. The upper bill is black and the lower bill is red-orange.

Adult Female: Similar to the male, but her plumage is duller.

Breeding / Nesting

Berylline Hummingbirds are solitary in all aspects of life other than breeding, and the male’s only involvement in the reproductive process is the actual mating with the female. They neither live nor migrate in flocks, and there is no pair bond for this species.

Males court females by flying in a U-shaped pattern in front of them. He will separate from the female immediately after copulation. One male may mate with several females.

In all likelihood, the female will also mate with several males. The males do not participate in choosing the nest location, building the nest, or raising the chicks.

The cup-shaped nest is constructed by the female alone. She uses plant fibers that she weaves together. The outside of the nest is camouflaged with green moss. She lines the nest with soft plant fibers, animal hair, and feathers down, and strengthens the structure with spider webbing and other sticky material, giving it an elastic quality to allow it to stretch to double its size as the chicks grow and need more room. The nest is placed in a sheltered location, typically in a shrub, bush, or tree on low, thin horizontal branches.

The average clutch consists of two white eggs, which she incubates alone, while the male defends his territory and the flowers he feeds on. The young are born blind, immobile, and without any down.

The female alone protects and feeds the chicks with regurgitated food (mostly partially digested insects since nectar is an insufficient source of protein for the growing chicks). The female pushes the food down the chicks’ throats with her long bill directly into their stomachs.

As is the case with other hummingbird species, the chicks are brooded only the first week or two and are left alone even on cooler nights after about 12 days – probably due to the small nest size. The chicks leave the nest when they are about 7 – 10 days old.

Diet / Feeding

They primarily feed on nectar taken from a variety of brightly colored, scented small flowers of trees, herbs, shrubs, and epiphytes. They favor flowers with the highest sugar content (often red-colored and tubular-shaped) and seek out, and aggressively protect, those areas containing flowers with high-energy nectar.

They use their long, extendible, straw-like tongues to retrieve the nectar while hovering with their tails cocked upward as they are licking at the nectar up to 13 times per second. Sometimes they may be seen hanging on the flower while feeding.

Many native and cultivated plants on whose flowers these birds feed heavily rely on them for pollination. The mostly tubular-shaped flowers exclude most bees and butterflies from feeding on them and, subsequently, from pollinating the plants.

They may also visit local garden nectar feeders for some sugar water, or drink out of bird baths or water fountains where they will either hover and sip water as it runs over the edge; or they will perch on the edge and drink – like all the other birds; however, they only remain still for a short moment.

They also take some small spiders and insects – important sources of protein particularly needed during the breeding season to ensure the proper development of their young.

Insects are often caught in flight (hawking); snatched off leaves or branches, or taken from spider webs. A nesting female can capture up to 2,000 insects a day.

Males establish feeding territories, where they aggressively chase away other males as well as large insects – such as bumblebees and hawk moths – that want to feed in their territory. They use aerial flights and intimidating displays to defend their territories.

Hummingbird Resources

- Hummingbird Information

- Hummingbird Amazing Facts

- Attracting Hummingbirds to Your Garden

- Hummingbird Species

- Feeding Hummingbirds