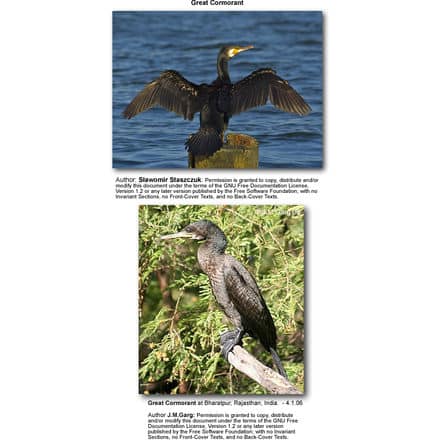

Great Cormorants also known as known as Great Black Cormorants

The Great Cormorants (Phalacrocorax carbo), known as the Great Black Cormorant across the Northern Hemisphere, the Black Cormorant in Australia and the Black Shag further south in New Zealand, is a widespread member of the cormorant family of seabirds. It breeds in much of the Old World and the Atlantic coast of North America.

Description

The Great Cormorant is a large black bird, 77-94 cm in length with a 121-149 cm wingspan. It has a longish tail and yellow throat-patch. Adults have white thigh patches in the breeding season. In European waters it can be distinguished from the Common Shag by its larger size, heavier build, thicker bill, lack of a crest and plumage without any green tinge.

In eastern North America, it is similarly larger and bulkier than Double-crested Cormorant, and the latter species has more yellow on the throat and bill.

Distribution

This is a very common and widespread bird species. It feeds on the sea, in estuaries, and on freshwater lakes and rivers. Northern birds migrate south and winter along any coast that is well-supplied with fish.

The type subspecies, P. c. carbo, is found mainly in Atlantic waters and nearby inland areas: on western European coasts and south to North Africa, the Faroe Islands, Iceland and Greenland; and on the eastern seaboard of North America, though in America it breeds only in the north of its range, in the Canadian maritime provinces.

The subspecies found in Australasian waters, P. carbo novaehollandiae, has a crest. In New Zealand it is known as the Black Shag or by its M?ori name; Kawau[1]

The 80-100 cm long White-breasted Cormorant P. c. lucidus found in sub-Saharan Africa, has a white neck and breast. It is often treated as a full species, Phalacrocorax lucidus (e.g. Sibley and Monroe, 1990, Sinclair, Hockey and Tarboton, 2002)

In addition to the Australasian and African forms, Phalacrocorax carbo novaehollandiae and P. carbo lucidus mentioned above, other geographically distinct subspecies are recognised, including P. c. sinensis (western Europe to east Asia), P. c. maroccanus (north-western Africa), and P. c. hannedae (Japan).

Some authors treat all these as allospecies of a P. carbo superspecies group.

Behavior

The Great Cormorant breeds mainly on coasts, nesting on cliffs or in trees (which are eventually killed by the droppings), but also increasingly inland. 3-4 eggs are laid in a nest of seaweed or twigs.

The Great Cormorant can dive to considerable depths, but often feeds in shallow water. It frequently brings prey to the surface. A wide variety of fish are taken: cormorants are often noticed eating eels, but this may reflect the considerable time taken to subdue an eel and position it for swallowing, rather than any dominance of eels in the diet. In UK waters, dive times of 20-30 seconds are common, with a recovery time on the surface around a third of dive time.

The Great Cormorant is one of the few birds which can move its eyes, which assists in hunting. [1]

Cormorants and humans

Many fishermen see in the Great Cormorant a competitor for fish. Because of this it was nearly hunted to extinction in the past. Thanks to conservation efforts its numbers increased. At the moment there are about 450,000 breeding birds in Western Europe. Increasing populations have once again brought the cormorant into conflict with fisheries, for example, in the UK where inland breeding was once uncommon, there are now increasing numbers of birds breeding inland and many inland fish farms and fisheries now claim to be suffering high losses due to these birds. In the UK each year some licences are issued to shoot specified numbers of cormorants in order to help reduce predation, it is however still illegal to kill a bird without such a licence.

Chinese fishermen sometimes tie fishing line around the throats of cormorants, tight enough to prevent swallowing, and deploy them from small boats. The cormorants “eat” fish without being able to fully swallow them, and the fishermen are able to retrieve the fish simply by forcing open the cormorants’ mouths, apparently engaging the regurgitation reflex.

References

- Barrie Heather and Hugh Robertson, “The Field guide to the Birds of New Zealand”(revised edition), Viking, 2005

- Sibley, C. G., and Monroe, B. L. (1990). Distribution and taxonomy of birds of the world. New Haven CT: Yale University Press.

- Ian Sinclair, Phil Hockey and Warwick Tarboton, SASOL Birds of Southern Africa (Struik 2002) ISBN 1-86872-721-1