Velvet Worm Life Cycle

Velvet worms are intriguing – bizarre even – in many ways.

Onycophorans are surprisingly skillful hunters. They are the only invertebrates that can shoot slime as a weapon.

Their skin is velvety and waterproof, and despite being called “worms,” they move more like millipedes on their chubby legs with tiny claws. Some species are social and live in complex groups with a strict hierarchy, ruled by a dominant female.

Another one of their peculiarities is their life cycle – the way they reproduce and give birth to their offspring.

If you think that the term “give birth” feels a bit misplaced when talking about “worms,” read on and be surprised.

How Do Velvet Worms Reproduce?

There are around 230 species of velvet worms, and they are all quite similar anatomically. However, the small differences in their environments made them evolve different ways of reproduction – and basically cover all modes we see in the invertebrate world!

Onychophoran modes of reproduction include

- Asexual (parthenogenesis, reproduction without males) – one species only.

- Egg-laying (Oviparity).

- Egg-live-bearing (Ovoviviparity, egg incubation within the mother’s body and then seemingly giving birth to live young).

- Live-bearing – Viviparity (giving birth to live young that develop inside the mother and are nourished in the uterus)

Let’s take a peek at each of these velvet worm reproductive strategies.

Parthenogenetic Velvet Worms

Only a single species of velvet worm reproduces asexually – with no mating or fertilization involved. However, it has allowed Onycophornas to check another box on the list of weird reproductive strategies.

Epiperipatus imthurni is a velvet worm so far found in Guyana and Trinidad. No males of these species were ever discovered; thus, scientists firmly believe that females reproduce via parthenogenesis.

Also known as “virgin birth,” parthenogenesis is a form of reproduction in which the egg cell divides and develops into an embryo without fertilization by sperm. The females are practically self-reproducing because genetic material doesn’t mix, and males… Well, they don’t exist (sorry, guys). Thus, the offspring is a genetic clone of their momma.

Oviparous Onychophora

In velvet worms, we observe egg-laying only in the more primitive family Peripatopsidae. The oviparous species mostly live in habitats with unstable climates (Australia and South Africa, for example), at least when compared to tropical species.

To make up for potential food scarcity and sudden weather changes, eggs of the egg-laying Onychophorans have rich yolks and protective shells made out of chitin.

Ovoviviparous Onychophora

The majority of velvet worms practice a confusing-sounding strategy of egg-live-bearing. How can an animal lay eggs and give birth at the same time?

In the ovoviviparous species, the mother velvet worm acts like a living incubator for her eggs which are regular medium-sized eggs with a modest amount of yolk.

The young emerge from the eggs shortly before birth. Unlike true live-bearers, there is no direct connection between the mother’s body and the embryo – the mother doesn’t feed the developing young directly.

It is thought this was the original reproduction mode of modern velvet worm ancestors. Then, depending on the environmental conditions, some species developed oviparity, while others – the ones you’re about to meet if you keep on reading, evolved viviparity.

Viviparous Onychophorans

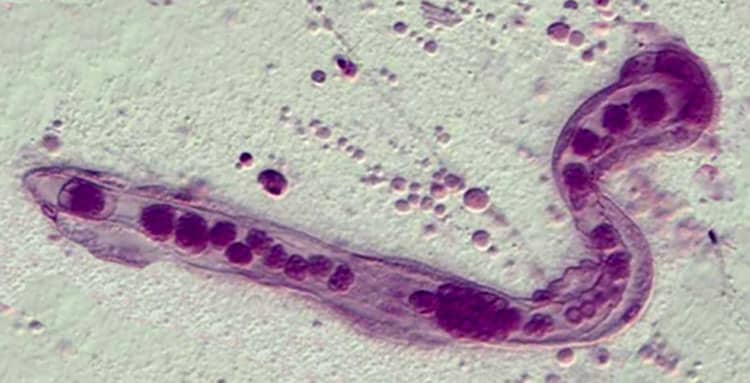

Quite a large chunk of velvet worm species – about 86 – give birth to live young, with embryos developing in a uterus-like organ inside the mother’s body.

With some species, there is a true placenta, and developing baby worms are directly connected to the uterus. In others, the nutrients are secreted into the uterus without tissue connection.

The mother can carry the young for up to 15 months, and the embryos can be of different ages and even descend from different males. They’re born as fully formed, miniature velvet worms.

As previously suggested, viviparous velvet worms mostly come from tropical regions with a stable climate and abundant food supply throughout the year.

What does “Weird reproduction” mean, exactly?

Even though we find it strange that a worm-like creature could give birth to live young much like our species, live-bearing is not that uncommon in the invertebrate world.

Remember – there are no true “weird” behaviors in nature because every reproductive strategy makes perfect evolutionary sense for that particular species.

For example, egg-laying onychophorans occur where the resources are scarce, and it would be too demanding to grow young in the mother’s uterus. According to the same pattern, their live-bearing cousins live in more fruitful habitats.

How Do Velvet Worms Mate?

Now you’re familiar with how velvet worm babies are born. Still, we haven’t yet covered how they’re made.

Velvet worm mating is strange on its own and includes an even greater number of strategies than the development.

All velvet worm species have internal fertilization, but most do not practice copulatory mating – only some members of the Paraperipatus genus have a true penis.

Instead, the male has to find a way to transfer his sperm, usually in the form of a spermatophore (a sperm ball), to the female’s genital opening. The array of their strategies across species is quite impressive – and still not fully known.

Here are some creative examples:

- In many species, such as Macroperipatus torquatus, females are fertilized only once during their lifetime, keeping the sperm in a special internal reservoir that preserves their viability.

- Males of some species have special structures on their heads, in the shape of dimples, depressions, spines, hollow stylets, and various blades they use to carry the ready-sperm package around. This structure can also play a role in spermatophore positioning.

- The male of Florelliceps stutchburyae has a long spine that is moved against the genital opening of its female partner to place the spermatophore.

The most bizarre breeding habit is the one that belongs to a couple of species from the genus Peripatopsis.

Instead of aiming for the genital opening on the female’s rear end, the male deposits the spermatophore on a random spot on the female’s body – usually the back.

Then, something strange happens. The female’s immune cells break down the skin on the inside of where the sperm package lies, practically creating a self-inflicted wound. The sperm then enters the female’s body and finds its way to the female’s ovaries.

The greatest mystery is why the wound doesn’t get contaminated since hurt velvet worms are quite prone to bacterial infections. One hypothesis is that the internal enzymes that create the injury also neutralize the pathogens.

How Long Does a Velvet Worm Live?

The precise lifespans of all velvet worm species are still unknown. Still, some are thought to live for about five years, which is likely the case with many others as well.

To Sum It Up

Like they haven’t been strange and interesting enough already, Onychophorans also have an amazing array of mating and reproduction strategies.

- Velvet worms employ various fertilization techniques that include bizarre specifics – from sperm-carrying sperm structures to self-inflicted wounds.

- Most species give birth to live young, with some incubating their eggs inside of them and others having embryos attached to the mother’s uterus – yes, much like in mammals. Others lay eggs, and one all-female species reproduces asexually via parthenogenesis.

Although this may all seem weird, remember that all these methods make perfect sense from an evolutionary standpoint – each species has evolved adaptations that give it the best chances of survival and reproduction in its native environment.

The point of that wound-generating sperm ball in the “lucky” Peripatopsis species may remain a bit of a mystery, though.

Resources

- Matrotrophy and placentation in invertebrates: a new paradigm (2015. A.N. Ostrovsky et. al, Biological Reviews)

- New Zealand peripatus/ngaokeoke (New Zealand Department of conservation)

- The Creature Feature: 10 Fun Facts About Velvet Worms (2014, M. Bates, Wired)

- The Onychophora of Trinidad, Tobago and the Lesser Antilles (1988, V. M. ST.J. Read, Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society)

- Velvet worm. (Australian Museum)