Gastropod Life Cycles 101: From Trochophore To Veliger Larva & Beyond

Gastropod life cycles are varied, particularly in relation to where development takes place – and how long development takes. Developmental biology (commonly the first part of an animal’s life cycle) is the biology of that part of an organism’s life from fertilization of the ova, to it becoming an adult. For most invertebrates this is an extremely dangerous time of life. Only a very small percentage of hatched young reach reproductive maturity.

The basic gastropod life cycle starts with fertilization and moves through the stages of embryo, trochophore larva, veliger larva and juvenile before becoming an adult.

The step from veliger larva to juvenile is a true metamorphosis. In some species, scientists observe additional named stages across the embryo stage.

Furthermore in many species of gastropods, especially terrestrial forms and those that brood their ova, some, or all of, these stages occur within the egg. What emerges from the egg is partially developed to different degrees in different species. At its simplest it is the trochophore larva, at its most developed it is a juvenile snail.

In all terrestrial species fertilization is internal and development within the egg is complete, whether the eggs are brooded or not. This means you do not see any of the larval forms in terrestrial species; what hatches from the egg is a juvenile. A juvenile is a fully formed snail or slug but is not yet sexually mature. In aquatic species what hatches from the egg varies between species.

Keep reading to find out more about the gastropod life cycle, or skip ahead directly to the section that interests you with the below links:

Nurse Eggs

Many species of egg laying animals, from chickens to sharks, frogs and various invertebrates include a degree of food or nutrient material within the laid egg – to allow for growth within the shell. Laying nurse eggs (sometimes called care eggs) is something females do to give their young a good start on their life cycle. The sole purpose of nurse eggs is to act as food for new hatchlings. Nurse eggs are eggs that are infertile and can never develop into anything. They are created and laid specifically to act as food, however their occurrence is quite rare.

Among the gastropods this is most frequently seen in marine species that lay their eggs inside capsules. This makes sense because the capsules can easily contain the nurse eggs, ensuring they are available to the larva when they hatch. In species with pelagic eggs this would be impossible.

The number of nurse eggs supplied by the mother and the number eaten during development varies considerably between species. Nurse egg consumption can average from as little as 1.7 nurse eggs per embryo, Acanthinucella spirata, to over 50,000 nurse eggs per embryo in Volutopsius norwegicus.

Furthermore the nurse egg to embryo ratio varies from capsule to capsule within a single clutch. In Lirabuccinum dirum for example it can vary from 11 to 46 across capsules. However, within a single egg capsule there is normally little variation in the number of nurse eggs eaten by each embryo.

The time a larval marine snail lives inside the capsule and feeds on the supplied nurse eggs can vary from one or two weeks to several months. However the end result is always that what emerges from the egg capsule is a fully formed juvenile snail. In species that do not supply nurse eggs, what escapes from the egg capsule can be either a juvenile or a veliger larva.

Gastropod Life Cycles and Egg cannibalism

This is not the same as newly hatched larva feeding on nurse eggs because the eggs fed on would have developed into larva themselves had they not been predated.

Egg cannibalism can occur when some eggs in a batch of eggs hatch before others. The juveniles that hatch out first feed on their unhatched brothers and sisters. The occurrence of egg cannibalism is quite frequent in terrestrial species with complete development within the egg and in marine species with encapsulated eggs; however it also occurs in some freshwater species.

Egg Cannibalism in Terrestrial Species

A newly hatched terrestrial snail does not immediately leave the nest and start feeding.

For most species it takes 4 to 8 days for the hatchlings to find their first plant food. In their soil-buried nest the only possible food is other eggs that are close nearby. Research on Helix adspersa indicates that the consumption of one, or most of one, conspecific egg gives hatchling snails a considerable survival advantage.

Arianta arbustorum is a terrestrial land snail from Europe in which egg cannibalism is common. In this species, not only will new hatchling eat other unhatched eggs in their own egg batch, but they will actively seek out other nearby egg batches to feed on. Scientific study has shown that cannibalistic individuals of Arianta arbustorum have far greater success in reaching adulthood than individuals unable to feed on eggs (66.6% vs 38.0).

Egg Cannibalism in Freshwater Species

Pomacea canaliculata is a freshwater gastropod native to southern South America. It is a highly successful invasive species, and as well as juvenile egg cannibalism, adults are known to feed on egg masses – both of their own species and of others. One unusual aspect of this is that the eggs of Pomacea canaliculata contain defensive and anti-nutritive compounds that apparently dissuade almost all potential predators, but these chemicals do not appear to work against their own conspecifics.

Egg Cannibalism in Marine Species

Egg cannibalism has been frequently observed in marine species. Crepidula coquimbensis is a species of slipper limpet that lays its eggs in small capsules, which are then brooded under the shell of the female. Development is complete within the egg and egg cannibalism is common. C. coquimbensis is a polyandrous species, meaning the eggs of a single female are fathered by several, or many males. Because of this there may be genetic perspectives controlling feeding choice in newly hatched juveniles.

Scientific research has shown that this species exhibits a degree of selectivity in who eats who. To quote the authors of the research.

“Our results show that the intensity of sibling cannibalism increased in aggregations characterized by the lowest level of relatedness. There were important benefits of cannibalism in terms of hatching cannibal size. In addition, cannibalism between embryos was not random: the variation in reproductive success between males increased over the course of the experiment and the effective number of fathers decreased. Altogether, these results suggest that polyandry may play an important role in the evolution of sibling cannibalism in C. coquimbensis and that kin selection may operate during early embryonic stages in this species.“

Juvenile Cannibalism

Juvenile cannibalism is less common but not rare among predatory marine gastropods such as whelks. Whelks are a common and successful group of carnivorous marine gastropods. They feed by using their radula to drill a hole in another shellfish and then draw out the flesh.

The Asian Rapa Whelk (Rapana venosa) is an aggressive species that is native to the northern pacific coasts of Asia and it is extensively farmed in China (Where it accounts for 20% of the local gastropod production). It has become an invasive pest in many other parts of the world.

Scientific research indicates that cannibalism is one of the leading causes of juvenile mortality in R. venosa to the extent that if other prey species were not available, this behaviour would endanger its own existence. However these whelks prefer to feed on bivalves and cannibalism usually only becomes a response to prey scarcity as the juveniles grow larger. Hexaplex trunculus the Banded Dye-murex is another predatory marine snail in which high levels of juvenile cannibalism have been observed.

Other Forms of Cannibalism

Adults attacking and feeding on juveniles of their own species is a known behaviour from gastropods. Although it has been reported from commonly named Cannibal Snail (Euglandina rosea) scientific analysis reveals that this behaviour is extremely rare. Euglandina rosea much prefers to feed on other species of snail, meaning it is mis-named.

Cannibalism of adults by other adults is also extremely rare. However it has been observed in the New Zealand Schizoglossa novoseelandica

The Trochophore Larva Stage of a Gastropod Life Cycle

In the classical aquatic gastropod (and other mollusc) life cycle, what hatches from the egg does not look much like the adult form and is called a “trochophore” or a “trochophore larva”.

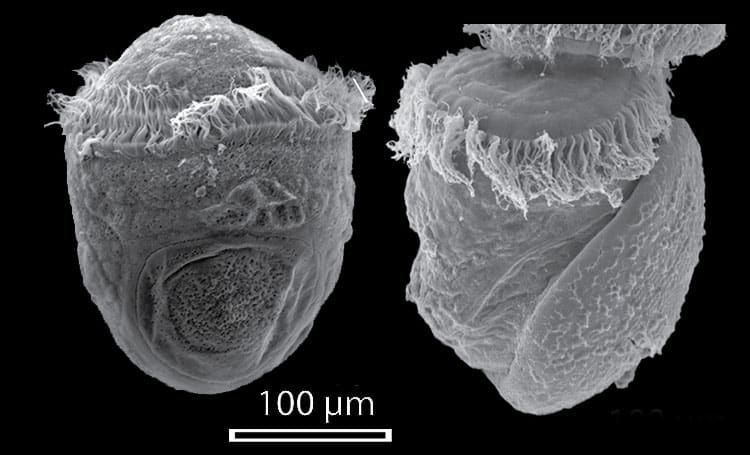

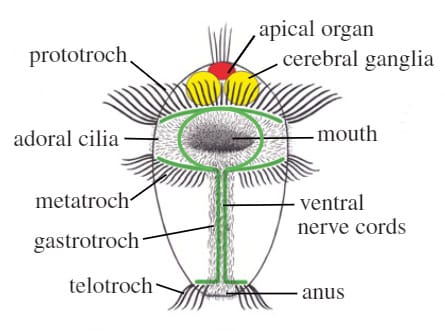

The trochophore larvae is a roughly globular shaped simple organism with two girdles of fine moveable hairs called “cilia” around the widest mid-part of its body. and a tuft of cilia at the apex.

This “ciliary girdle” is what allows the animal to move through the water. The upper ciliary girdle is called the “prototroch” and the lower one is called the “metatroch”; there can be other much shorter cilia in between these two rows of cilia called “adoral cilia”. In non-feeding forms the metatroch is usually absent. Further terminology is used for the stomach, “gastrotroch” and the anus “telotroch”.

The ciliary girdle is in constant movement and collects and guides food particles to the mouth (in feeding forms). The mouth is also lined with smaller cilia that move the food to the stomach for digestion and eventual excretion through the anus. Apart from these ciliated organs the trochophore possesses two small ganglia, a few basic nerve cords and, in some cases, an ocellus (simple eye). Finally they contain a few other simple organs such as a solenocyte, whose function seems to be to maintain proper internal salt-water (ionic) balance.

In some species of marine gastropod such as the netted Dog Whelk (Nassarius reticulatus), the trochophore stage is passed inside the egg capsule. These pellucid and sometime pelagic larva are produced in huge amounts by some species to become part of the ocean’s zooplankton. They drift in the currents and feed on anything that is small enough to enter their mouths.

Trochophore larva are constantly changing, they are not a static state of existence, but a process of becoming that moves the animal from being a developed embryo to the next stage of life, the veliger larva.

Veliger Larva Stage of a Gastropod Life Cycle

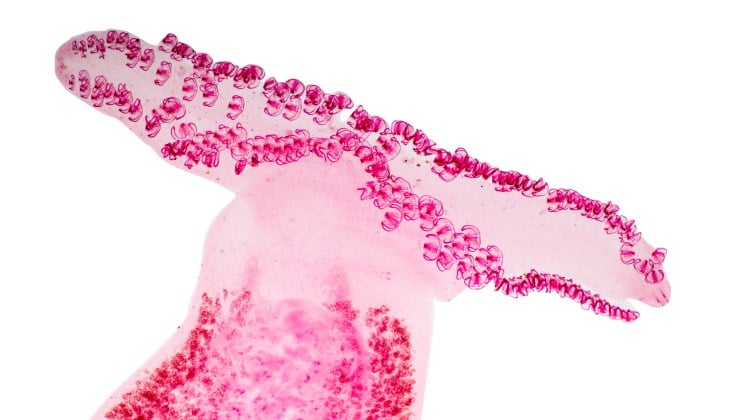

In time, as the gastropod life cycle unfolds (varying from a few hours to several days), the ciliary girdle of the trochophore larva develops two fleshy side growths; a bit like wings, these are called vela. At this stage, the young animal is called a “veliger larva”.

Planktonic veliger larva feed on micro-plankton (diatoms, pelagic eggs and smaller aquatic larva of other species). These food items are collected and directed to the animal’s mouth by the action of the cilia, now arranged along the vela.

Veliger larva can take from a few days to several months before it metamorphosizes into a post larva, depending on where the development is taking place. In species where the development is all within the eggs, development is usually much quicker than for species with planktonic larva that have to find their own food.

Veliger larva that come from pelagic trochophore larva have no store of food to draw on, however veliger larva that have escaped from an egg capsule may bring with them some egg yolk material. Some will be able to develop fully on this stored material, but others will need to spend some time feeding in the plankton soup of the ocean to complete their development.

Before veliger larva can metamorphosize, they need to develop the organs they will need to survive as benthic juveniles. Also it is during this second larval stage that the animal begins to develop its shell, something it will need when it settles to the ocean floor. The first part of the shell visible in a veliger larva is called the “protoconch”. However by the time the snail is ready to metamorphosize, it has a diminutive but recognizably coiled shell. This shell is usually white or translucent.

Organ Development in Veliger Larva

As the veliger larva progresses, so it develops many of the characteristic features of the adult snail – such structures as a muscular foot, eyes, rhinophores, a fully developed mouth, and a spiral shell.

Strangely, the veliger larva of nudibranchs possesses a shell even though adult nudibranchs do not possess a shell.

Eventually the veliger larva allows itself to sink to the ocean floor where it can undergo its metamorphosis into a juvenile.

When it begins its metamorphosis into a benthic juvenile, the animal absorbs the vella that allowed it to swim, and turns this material into other internal organs. It is during the final days of the veliger larva stage of its life cycle, that a gastropod undergoes torsion the twisting of the body through 180 degrees so that the posterior part of the body and the anus end up just behind the head). The process of becoming torted can be very quick and happen in just a few minutes, or it can take as long as ten days.

Exactly what triggers the final descent into metamorphosis once the veliger is sufficiently developed is poorly understood. However in some cases it seems to involve the detection of chemicals associated with a suitable habitat for the juvenile, and adults, of that species to live in. Possibly these chemicals are indicative of the presence of adults and juveniles on the ocean floor below. Without some mechanism like this, a planktonic veliger larva could end up becoming a juvenile in a completely unsuitable habitat.

Juvenile Gastropods

The juvenile animal is a smaller and sexually immature version of the adult it will become. From here on it it is simply matter of feeding and growing to reach sexual maturity, in order to become an adult snail. Juveniles tend to follow similar lives to their fully adult counterparts. The length of time spent as a juvenile is variable. Some species can reach sexual maturity in as little as six weeks, where as others may take six months.

To learn more about gastropods why not take a look at Gastropod Reproduction or Gastropod Ecology (living everywhere) – coming soon.

Image credits:- Cover image by Michal Maňas, – license CC BY-SA 4.0; ESM images of Halioti asinina by Daniel J Jackson, Gert Wörheide and Bernard M Degnan; Nudibranch Laying Eggs by Ed Bierman; – license CC BY 2.0 ; Voluta magnifica hatching and Unidentified Veliger larva courtesy of and copyright to Denis Reik